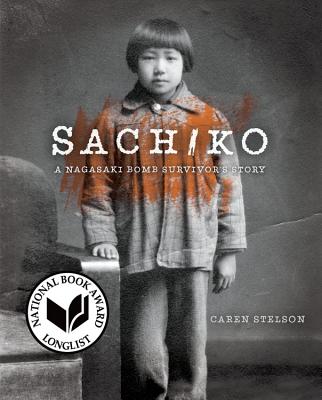

In the back matter, you tell us how you first learned Sachiko’s story and how you traveled to Japan multiple times to meet with her. Will you please tell us more about these meetings? Where did you meet? What was it like talking through a translator? What did you talk about? What did you do when you and Sachiko weren’t meeting?

My meetings with Sachiko are forever pressed into my memory. Translator Dr. Takayuki Miyanishi, Sachiko and I would huddle in a room in a Nagasaki library or at Nagasaki University, press the recording button, and talk for hours. Dr. Miyanishi would simultaneously translate in English softly, without emotion, as Sachiko spoke directly to me. It’s funny, but I can’t really remember Takayuki’s translation, only Sachiko’s voice speaking in Japanese and her expressions. Obviously, I was listening intently to the translation because I don’t speak Japanese. I described this intense listening to a friend as listening through my skin.

I am forever grateful to Dr. Miyanishi for his dedication and willingness to spend hours of his valuable time with Sachiko and me. Dr. Miyanishi is a professor of Environmental Science at Nagasaki University as well as president of the Nagasaki-Saint Paul Sister City Committee. He insisted that all the time he spent during my five interview visits to Nagasaki were well worth it. Even though Dr. Miyanishi lived in Nagasaki, he had never really heard a survivor’s story like Sachiko’s, either.

What did I do after our interviews? Plenty. Every breathing minute in Nagasaki was research. I took note of the weather, the sounds of the cicadas, the sparkling water of the Nagasaki harbor. I took photos of my meals at restaurants and savored the food while eating with chopsticks. I toured Nagasaki and visited places near Sachiko’s neighborhood, such as the Sakamoto Cemetery and the 500-year-old camphor trees. I spent hours in the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and countless more interviewing other atomic bomb survivors and subject matter experts who could share information related to the book.

I didn’t always stay in Nagasaki when I traveled to Japan. On one trip I spent time in Hiroshima and participated in a week- long peace seminar at the Hiroshima City University. I also traveled to Tokyo to do primary research in the Diet Library, equivalent to our Library of Congress. When I returned home I’d read, read, read whatever related to Sachiko’s story. At night before I went to bed, I would read haiku out loud to keep the music and the sparse beauty of the Japanese language in my mind.

Are there any parts of your research that you thought were interesting but were not able to fit in the book?

I had a lot of information I left out of the book. I’m sure most nonfiction writers will nod in agreement. I read stacks of books just for background information. The question was how much history should be included on the gray informational pages of the book. For example, I read entire books about the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. At first I thought this event should be included in the body of the book, but eventually I decided against it. The Cuban Missile Crisis has stayed with me and is a critical event, but it was not an indelible memory for Sachiko, or for other Japanese people I interviewed. Instead, I decided to add the details of the Cuban Missile Crisis to the historical notes in the back of the book.

There were other details left out that were of a more personal nature. For example, I didn’t develop Sachiko’s relationship with her youngest sister Etsuko. Etsuko was born after the atomic bombing and was never part of Sachiko’s story when Sachiko spoke publically about her life. Although Sachiko never placed restrictions on my writing of her story, I had to respect the boundaries between Sachiko’s “public” story and her private life.

What do you hope your readers will take away from Sachiko’s story?

What do you hope your readers will take away from Sachiko’s story?

First, I want my readers to recognize the power of Sachiko’s story, the horror of her experience as a hibakusha, an atomic bomb survivor, and the courage it took to live her life. But there’s more, much more. Mostly I want my readers to rethink what peace means. Peace is not sitting under a tree on a sunny afternoon. Peace is active. Peace takes courage to stand up for what you believe. Working for peace doesn’t come easily. We all need to study peace and justice and understand the power of empathy, understanding, and reconciliation. Our American culture bends towards war and violence. We have enough guns in the United States for every man, woman and child. More than ever, we need to find ways to bend towards peace, individually and in community, and to take seriously Sachiko’s words: “What happened to me must never happen to you.”

What can young readers do to help end nuclear war?

What a huge question! It seems impossible to contemplate for any of us, no matter what our age. But it’s not impossible. Young people can help end nuclear war. I have great faith that the younger generations will be our next generation of peacemakers. Young people can start preparing themselves by learning about the destructive power of nuclear weapons and the reasons we have them. They can read about the Cold War of nuclear proliferation and ask themselves if this is history they would like to see repeated. I challenge young people to find their own mentors of peace in history and in their communities and ask what characteristics do these mentors have in common. Young people can cultivate those characteristics of empathy, determination, and resilience. I encourage young people to reach out in service in areas that bring them fulfillment, step into leadership roles, and invite others to join them in making a difference. I urge young people to pay close attention to national and world events. Learn the difference between news, fake news, and propaganda. Practice speaking in public about what they value most. When young people turn 18–vote. Run for office. Participate in our democracy. If we all actively work for peace, not just young people, we can prevent nuclear war.

What tips do you have on research and nonfiction writing for other authors?

Tips I have for nonfiction writers are the same tips I try to keep in mind for myself: (1) Be choosey about your subject. You may be living with this story for years. Make sure you are passionate—no, obsessed–about the story you want to tell. Your passion and energy will keep you going even when you hit the inevitable days of discouragement and frustration. (2) Do your research. Dig deep. Go where you are scared to go. (3) Look for powerful themes and use them as threads to help stitch the story together. (3) Use the tools of fiction to bring out the story. Where can you use dialog? Reach for specific detail. Follow the arc of the story. Remember, just as a writer of fiction, you too are writing a compelling story. But unlike fiction, you can’t make it up. Everything must be true.

Thank you so much for your time!